A Story Behind The Four-Way Test

By Darrell Thompson

More than 60 years ago, in the midst of the Great Depression, a U.S. Rotarian devised a simple, four-part ethical guideline that helped him rescue a beleaguered business. The statement and the principles it embodied also helped many others find their own ethical compass. Soon embraced and popularized by Rotary International, The Four-Way Test today stands as one of the organization’s hallmarks. It may very well be one of the most famous statements of our century.

Herbert J. Taylor, author of the Test, was a mover, a doer, a consummate salesman and a leader of men. He was a man of action, faith and high moral principle. Born in Michigan, USA, in 1893, he worked his way through Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois.

Herbert J. Taylor, author of the Test, was a mover, a doer, a consummate salesman and a leader of men. He was a man of action, faith and high moral principle. Born in Michigan, USA, in 1893, he worked his way through Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois.

After graduation, Herb went to France on a mission for the YMCA and the British Army welfare service and served in the U.S. Navy Supply Corps in World War I. In 1919, he married Gloria Forbrich, and the couple set up housekeeping in Oklahoma, USA, where he worked for the Sinclair Oil Company. After a year, he resigned and went into insurance, real estate and oil lease brokerage.

With some prosperous years behind him, Herb returned to Chicago, Illinois, in 1925 and began a swift rise within the Jewel Tea Company. He soon joined the Rotary Club of Chicago. In line for the presidency of Jewel in 1932, Herb was asked to help revive the near-bankrupt Club Aluminum Company of Chicago. The cookware manufacturing company owed $400,000 more than its total assets and was barely staying afloat. Herb responded to the challenge and decided to cast his lot with this troubled firm. He resigned from Jewel Tea, taking an 80 percent pay cut to become president of Club Aluminum. He even invested $6,100 of his own money in the company to give it some operating capital.

Looking for a way to resuscitate the company and caught in the Depression’s doldrums, Herb, deeply religious, prayed for inspiration to craft a short measuring stick of ethics for the staff to use.

As he thought about an ethical guideline for the company, he first wrote a statement of about 100 words but decided that it was too long. He continued to work, reducing it to seven points. In fact, The Four-Way Test was once a Seven-Way Test. It was still too long, and he finally reduced it to the four searching questions that comprise the Test today.

Next, he checked the statement with his four department heads: a Roman Catholic, a Christian Scientist, an Orthodox Jew and a Presbyterian. They all agreed that the Test’s principles not only coincided with their religious beliefs, but also provided an exemplary guide for personal and business life.

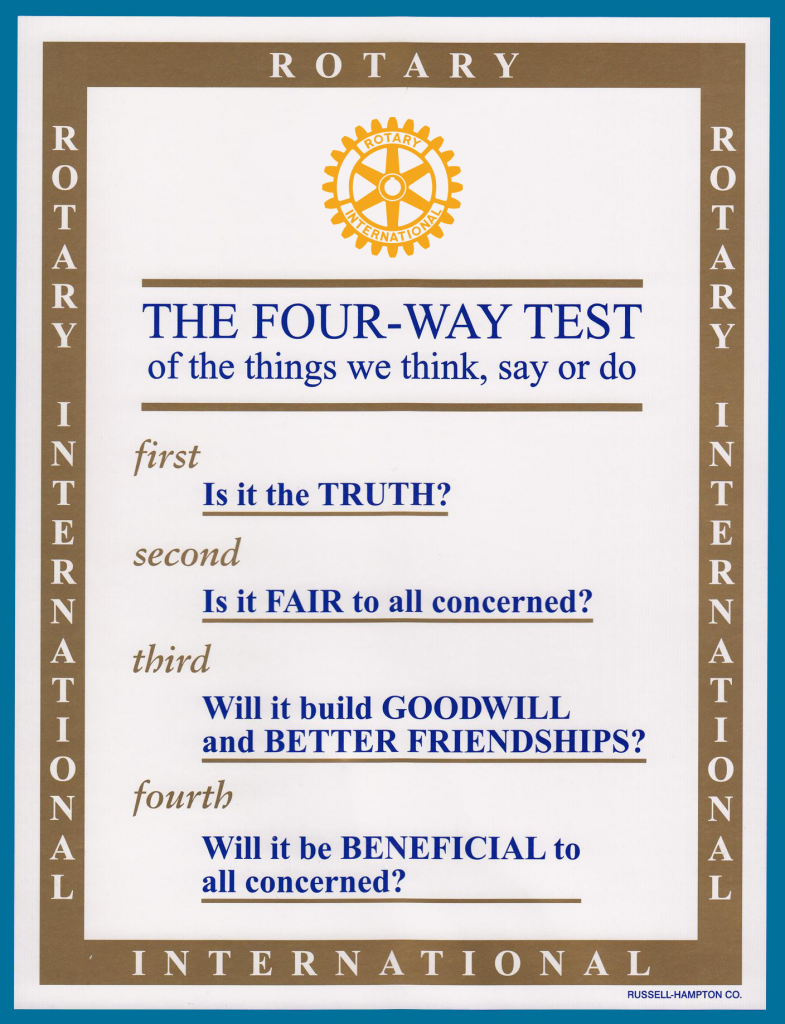

And so, “The Four-Way Test of the things we think, say or do” was born:

Is it the TRUTH?

Is it FAIR to all Concerned?

Will it build GOODWILL and BETTER FRIENDSHIPS?

Will it be BENEFICIAL to all concerned?

Profound in its simplicity, the Test became the basis for decisions large and small at Club Aluminum.

But any test must be put to the test. Would it work in the real world? Could people in business really live by its precepts? One lawyer told Herb: “If I followed the Test explicitly, I would starve to death. Where business is concerned, I think The Four-Way Test is absolutely impractical.”

The attorney’s concerns were understandable. Any ethical system that calls for living the truth and measuring actions on the basis of benefits to others is demanding. Such a test can stir bitter conflict for those who try to balance integrity and ambition. Sizzling debates have been held in various parts of the world on its practicality as a way of living. There are always some serious-minded Rotarians, not to mention skeptics and negative thinkers, who view The Four-Way Test as a simplistic philosophy of dubious worth, contradictory meaning and unrealistic aims. The Test calls for thoughtful examination of one’s motives and goals. This emphasis on truth, fairness and consideration provide a moral diet so rich that it gives some people “ethical indigestion.”

But at Club Aluminum in the 1930s, everything was measured against The Four-Way Test. First, the staff applied it to advertising. Words like “better,” “best,” “greatest” or “finest” were dropped from ads and replaced by factual descriptions of the product. Negative comments about competitors were removed from advertising and company literature.

The Test gradually became a guide for every aspect of the business, creating a climate of trust and goodwill among dealers, customers and employees. It became part of the corporate culture, and eventually helped improve Club Aluminum’s reputation and finances.

One day, the sales manager announced a possible order for 50,000 utensils. Sales were low and the company was still struggling at the bankruptcy level. The senior managers certainly needed and wanted that sale, but there was a hitch. The sales manager learned that the potential customer intended to sell the products at cut-rate prices. “That wouldn’t be fair to our regular dealers who have been advertising and promoting our product consistently,” he said. In one of the toughest decisions the company made that year, the order was turned down. There was no question this transaction would have made a mockery out of The Four-Way Test the company professed to live by.

By 1937, Club Aluminum’s indebtedness was paid off and during the next 15 years, the firm distributed more than $1 million in dividends to its stockholders. Its net worth climbed to more than $2 million.

Too idealistic for the real world? The Four-Way Test was born in the rough and tumble world of business, and put to the acid test of experience in one of the toughest times that the business community has ever known. It survived in the arena of practical commerce.

In 1942, Richard Vernor of Chicago, then a director of Rotary International, suggested that Rotary adopt the Test. The R.I. Board approved his proposal in January 1943 and made The Four-Way Test a component of the Vocational Service program, although today it is considered a vital element in all four Avenues of Service.

Herb Taylor transferred the copyright to Rotary International when he served as R.I. president in 1954-55, during the organization’s golden anniversary.

Today, more than six decades since its creation, has the Test lost its usefulness in modern society, as some critics maintain? Is it sophisticated enough to guide business and professional men and women in these fast-paced times?

Is it the TRUTH? There is a timelessness in truth that is unchangeable. Truth cannot exist without justice.

Is it FAIR to all concerned? The substitution of fairness for the harsh principles of doing business at arm’s length has improved rather than hurt business relationships.

Will it build GOODWILL and BETTER FRIENDSHIPS? Man is by nature a cooperative creature and it is his natural instinct to express love.

Will it be BENEFICIAL to all concerned? This question eliminates the dog-eat-dog principle of ruthless competition and substitutes the idea of constructive and creative competition.

The Four-Way Test is international, transcending national boundaries and language barriers. It knows no politics, dogma or creed. More than a code of ethics, it has all the ingredients for a successful life in every way. It can and will work in today’s society.

The final test is in the doing. William James, the noted psychologist, once said, “The ultimate test of what a truth means is the conduct it dictates or inspires.” At the heart of Rotary today is The Four-Way Test — a call to moral excellence. Human beings can grow together. Modern business can be honest and trustworthy. People can learn to believe in one another. At the 1977 R.I. Convention, James S. Fish of the U.S. Better Business Bureaus said, “To endure, the competitive enterprise system must be practiced within the framework of a strict moral code. Indeed, the whole fabric of the capitalistic system rests to a large degree on trust . . . on the confidence that businessmen and women will deal fairly and honestly, not only with each other, but also with the general public, with the consumer, the stockholder and the employee.”

Few things are needed more in our society than moral integrity. The Four-Way Test will guide those who dare to use it for worthy objectives: choosing, winning, and keeping friends; getting along well with others; ensuring a happy home life; developing high ethical and moral standards; becoming successful in a chosen business or profession; and becoming a better citizen and better example for the next generation.

Eloquently simple, stunning in its power, undeniable in its results, The Four-Way Test offers a fresh and positive vision in the midst of a world full of tension, confusion and uncertainty.

Darrell Thompson is a member of the Rotary Club of Morro Bay, California. This article is adapted from a speech given by Darrell, with contributions from Rotarians Douglas W. Vincent of Woodstock-Oxford, Ontario, Canada, and Myron Taylor.